Ending homelessness isn’t controversial—but how and where to do that can quickly draw opposition in many communities.

That’s the case in Norman, Oklahoma, where a temporary downtown shelter has drawn criticism from some residents and city councilmembers.

On Tuesday, the Norman City Council approved a month-to-month contract with nonprofit Food and Shelter to run the shelter. This vote followed a small daisy chain of short-term contracts with the nonprofit, which have left some residents worried about the shelter’s future.

The City Council heard comments from more than 20 residents, the majority of whom supported keeping the shelter open.

Katie Murray, a cooperative owner of Gray Owl Coffee, said her coffee shop is about two blocks away from the shelter. The number of unhoused people coming into the shop hasn’t changed since the shelter opened last year, she said.

“Like most of our patrons, houseless folks are just looking to exist somewhere that connects them to their community and just take a moment of peace in their busy days,” Murray said.

Resident Paul Wilson, who spoke in favor of the shelter, said that he and his wife previously experienced homelessness.

“A shelter helped us to get to where we are today,” he said. “Without a shelter, who knows where we would be?”

Other residents expressed concerns about the risks to unhoused people’s health outdoors in the grueling summer heat.

During the pandemic, the city created a homeless shelter using covid relief grants, but the shelter shut down a year ago as that federal funding evaporated. Norman selected Food and Shelter to run a city-funded, permanent, overnight shelter, said April Doshier, executive director of the nonprofit.

By that time, months had passed since the city’s shelter closed, and Norman needed a place where unsheltered people could stay warm during the winter months.

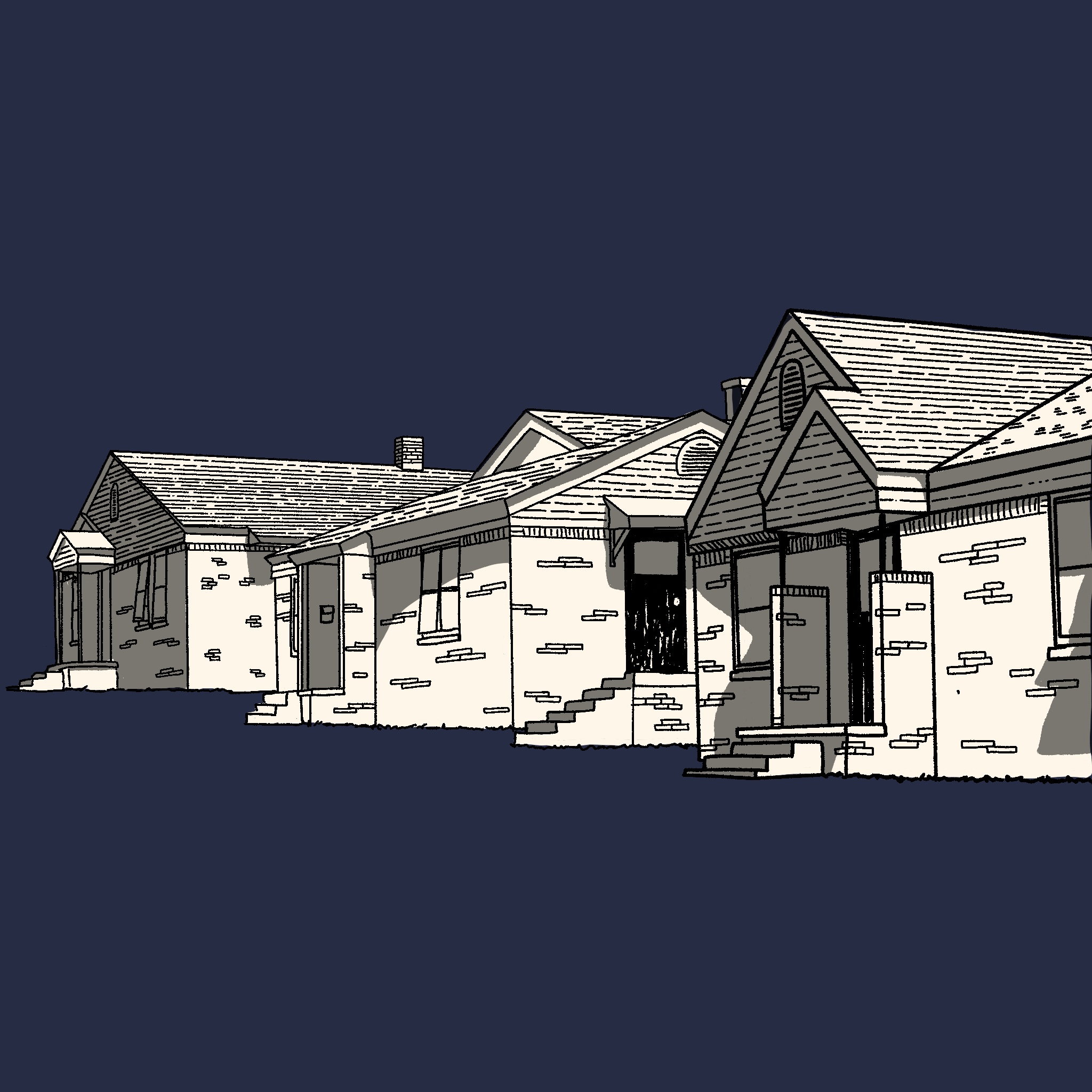

After receiving two short-term contracts with the city, Food and Shelter has operated its shelter on 109 W. Gray St. for about eight months leading up to this week’s city council meeting.

“There was always a plan in place for there to be a permanent location,” Doshier said. “There are a lot of opinions about where shelters should and shouldn’t be, and we have just gotten some hiccups along the way.”

The ideal location, Doshier said, would be close to Food and Shelter’s day services so that people could easily access resources like meals and case management.

Treatment first, housing first

The City Council approved the month-to-month shelter contract by a 6-to-3 margin, with councilmembers Rarchar Tortorello, Austin Ball and Mayor Larry Heikkila opposed.

During the meeting, Tortorello pushed the idea of “treatment first” services that would require unsheltered people to obtain substance use services before they can receive housing services.

Housing advocates across the country have said for years this approach is less successful than prioritizing housing resources that ensure people have the stability to deal with mental health and substance use issues. A 2022 plan to reduce homelessness in Norman and Cleveland County recommended this “housing first” approach.

[ Read more: In Oklahoma, corporate landlords are filing evictions without the legal right to sue ]

According to an analysis of homeless services in Norman and Cleveland County, 30% of people accessing those services from 2017 to 2019 had a mental health problem. The study said 12% had a substance use disorder.

For that group, “giving them a bed is not an answer,” Ball said during the late-night meeting.

“All we keep doing is throwing money at a temporary shelter over and over again, and that’s why everybody in this room is so frustrated,” he said.

Ball added that after he left the military, he dealt with drug addiction and experienced homelessness himself.

“The most compassionate thing anybody did for me was stop enabling that behavior,” he said. “They quit giving me handouts, they told me to grow up, get a job and get myself together. I never went to a shelter, I never took a handout from anybody.”

Among the recommendations from Norman and Cleveland County’s homelessness plan were to increase emergency homeless services and permanent supportive housing, which provides renters with support services. In March, city councilmembers approved $1.5 million for the construction of permanent supportive housing. The Norman Housing Authority will offer project-based housing vouchers for the apartment building.

Going forward, where unsheltered people can get help is likely to remain at least somewhat controversial in Norman. During the City Council meeting, one resident read local crime data, and another read a police report involving an unsheltered person who had slept in a laundry room. Several said they felt unsafe or worried about crime increasing because of the shelter.

Doshier believes comments like those don’t represent the community as a whole.

“As much as we hear the loud, angry cries of people who say, ‘You don’t belong here,’” she said, “there are many more people in Norman who say, ‘You do belong here, we love you and we’re here with you.’”

Contact Streetlight editor Mollie Bryant at 405-990-0988 or bryant@streetlightnews.org. Follow her reporting by joining our newsletter.

Streetlight, previously BigIfTrue.org, is a nonprofit news site based in Oklahoma City. Our mission is to report stories that envision a more equitable world and energize our readers to improve their communities. Donate to support our work here.