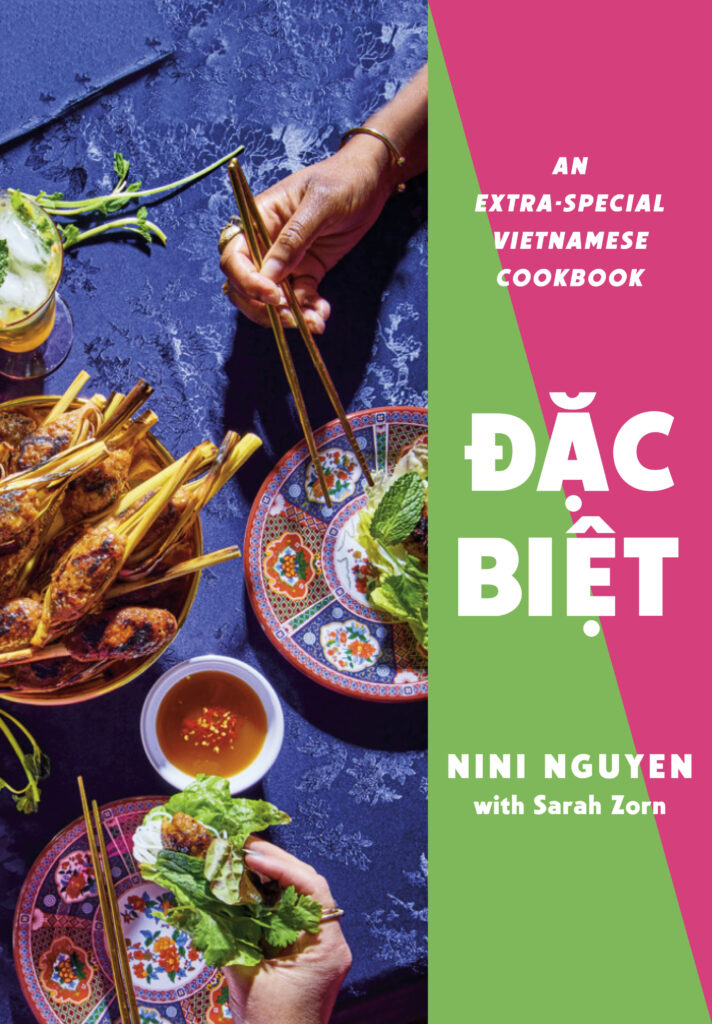

In vibrant green, pink and purple, celebrity chef Nini Nguyen’s ornate fingernail designs match the colors of her new cookbook just as easily as the costumes of a krewe marching in a New Orleans Mardi Gras parade.

Nguyen’s nails are Đặc Biệt, a Vietnamese expression that means extra special or luxurious and also is the title of her debut cookbook, written with Sarah Zorn. They’re not-so-subtle nods to her family upbringing, as many of the women in her family work in the nail salon industry, and over half of nail salons in the United States are Vietnamese-American owned.

And Nguyen’s color-coordinated nail art shows a hint of the style she lends to a cookbook filled with food photography that is a feast for the eyes as much as the stomach.

“I didn’t want it to look like all of the other Vietnamese cookbooks out there,” Nguyen said after her fundraising dinner for nonprofit Pivot with two-time James Beard finalist Jeff Chanchaleune at Birdie’s by Chef Kevin Lee in Edmond, Oklahoma on Aug. 30. “It was important for me to make a book that Vietnamese and Southeast Asian people will really see our heritage and culture in. I want Vietnamese people to be proud of what we’ve been through and what we came from.”

Nguyen’s effervescent personality, fashion choices and unabashed love for the Vietnamese community in New Orleans made her a fan favorite across two seasons of Bravo’s flagship culinary competition show Top Chef.

Nguyen’s commitment to representing Vietnamese cuisine on her own terms, her top-notch teaching techniques, well-tested recipes and a rollicking personal narrative that is equal parts tragedy and triumph, weaving in the impacts of thousands of years of colonial history, make “Đặc Biệt” not just a contender in its publishing genre, but one of the best books of the year.

Oklahoma City chefs find success in authenticity

Without context, the Oklahoma City area might seem like an unlikely destination for Ngyuen’s second stop on a national book tour, but it’s home to one of the largest Vietnamese-American communities in the country. Her fundraising dinner comes at a time when the city is experiencing a culinary breakout thanks in large part to practicing one of Nguyen’s hallmarks, representation.

Birdie’s Chef Kevin Lee brought Nguyen and her fellow Top Chef all-star Dale Talde into town for a weekend of two special-ticket dinners where Top Chef semi-finalist Josh Valentine joined them in the kitchen.

Chanchaleune initially hit it big on the OKC food scene with Japanese cuisine at Gorō Ramen, but it wasn’t until he started cooking iterations of his family’s Laotian recipes at Ma Der Lao that the accolades began to roll in. Bon Appétit named Ma Der Lao best new restaurant in 2022, and it’s only a matter of time until Chanchaleune wins best chef for the Southwest region at the James Beard Awards after being a finalist in 2023 and 2024.

Lee originally opened Birdie’s as a fast-casual Korean fried chicken restaurant in 2022. Lee took note of the success of Chanchaleune, as well as Zach Walter and Silvana Arandia-Walters at Sedalia’s Oyster and Seafood, a family-inspired Bolivian oysterette that was also named to Bon Appétit’s new restaurant superlative in 2023. So Lee retrofitted Birdie’s into a modern Korean steak house with table service and a high-end cocktail bar this year.

“(Ma Der Lao and Sedalia’s) are two of the reasons I was able to do this,” Lee said, referring to rebranding his restaurant to Birdie’s by Chef Kevin Lee. “They were cooking the food that they’re passionate about, they love. It’s not necessarily something you’d think the public would accept right away, but they took a chance, showcased their talent and people responded. The synergy we’re creating in Oklahoma City is really special.”

From tailgates to Manhattan’s finest

Like so many other Vietnamese immigrants to New Orleans, Nguyen’s maternal grandmother worked in the seafood industry. She’d wake up at 3 a.m. to begin a long day of shucking oysters before returning home to help raise eleven different family members before Nini and her brother came along. In 2004, Nguyen enrolled at the University of New Orleans, only for Hurricane Katrina to arrive a year later, sending her and her family to Baton Rouge, where she entered business school at Louisiana State University (LSU).

At football tailgates, Nguyen got a crash course in cajun and creole cuisine, which only heightened her passion to become a chef. After working in both the front and back of the house while finishing her degree at LSU, Nguyen defied conventional wisdom and landed a job at the ultra-prestigious, Michelin three-star restaurant Eleven Madison Park in Manhattan right out of college.

That’s where she refined her skills with 93-hour workweeks on both the savory and sweet side, even serving as pastry chef. Nguyen showcased those skills in “Đặc Biệt” with her recipe for bánh mì bread with detailed, step-by-step photos and an additional two-page spread on the perfect bánh mì architecture.

The cookbook provides similarly fastidious pictured instructions for making spring rolls, steamed rice rolls or bánh cuốn, bao, and bánh giò, a banana-leaf-wrapped pork, rice and mushroom dumpling. There’s even a robust dessert section featuring some of Nguyen’s Michelin-level pastry skills, as well as humble and delicious family recipes.

The recipes are detailed, often include additional cooking tips and were tested across the country as Nguyen enlisted 600 of her Instagram followers to collaborate and test five of her dishes. The cross section of testers allowed them to work through differences recipes might have between altitudes and heating surfaces.

Making a cookbook for Vietnamese people first

Those digestible, didactic sections throughout “Đặc Biệt” are indicative of Nguyen’s ease at teaching cooking. Techniques and skills she honed developing a cooking school in Brooklyn and when the covid pandemic required a permanent pivot to online cooking classes, along with the fact so many Vietnamese-Americans signed up for her classes provided the spark needed for her to write a cookbook.

“So many people would say, ‘You’ve been on TV. Let’s write a book,’ and I could see the opportunity in their eyes, but it didn’t benefit me because it wasn’t what I wanted,” Nguyen said. “Vietnamese people would come to my cooking classes, and it touched me because they would say, ‘I’m so happy because this tastes like my mom’s (cooking) and I lost my mom,’ or they can’t speak the same language. Or they’d want to assimilate (to American culture), which meant not eating or cooking Vietnamese food.”

In true Đặc Biệt fashion, Nguyen scoured her family’s belongings and keepsakes to showcase a truly representative experience of growing up Vietnamese in New Orleans, with bright red table cloths, gold plates and bright blue and neon green satin tablecloths. That also included using old Vietnamese newspapers as a tablecloth to make for easy cleanup after messy meals.

“You can’t be representative with (food photos) on a marble table top and noodles in a white bowl,” Nguyen said. “I want to see the just-picked herb stems at the side of the table. I want to see the types of chopsticks and plates on which we grew up eating because that’s what we had access to.”

“It was important to me to have every dish labeled in Vietnamese because a lot of cookbooks didn’t have that,” she added, “I guess because publishers thought Vietnamese people wouldn’t buy the book. I didn’t want to Americanize it. I love my publisher (Knopf under Penguin Random House) because I told them, ‘I’m writing this for Vietnamese people first. I hope you’re OK with that.’ They said yes.”

Have you eaten rice yet?

“Đặc Biệt” features many anecdotes that might surprise American audiences, like the fact phở grew in popularity after Bill Clinton visited Ho Chi Minh City in 2000.

“My goal (with the soup chapter) is to show people there is more than phở when it comes to Vietnamese noodle dishes,” Nguyen writes. “Don’t get me wrong, phở is my favorite hangover cure, along with most partygoers in New Orleans. But there are some noodle soups in Vietnam that would blow phở out of the water.”

The cookbook features ingredients Vietnamese immigrants adopted as replacements in the United States, like molasses, bouillon cubes and peanut butter.

“When my grandmother came to this country, she didn’t have access to Vietnamese ingredients, but it didn’t stop her from making Vietnamese food,” Nguyen said. “She made do with what she could find.”

At this point in our conversation, I couldn’t help but think of E.M. Tran’s “Daughters of the New Year,” one of my favorite books from this decade. Tran, who is also the first-generation daughter of Vietnamese immigrants in New Orleans, uses a fictionalized version of her family’s immigrant story to tell a sprawling, cross-generational narrative in reverse chronological order, beginning in present-day New Orleans and ending on the frontlines when warrior sisters charge into battle during the first-century uprising against Chinese rule—as time melts into a soup as clear as one of Nguyen’s recipes.

Much like on an episode of PBS’ “Finding Your Roots,” when a person’s genealogical history reveals unknown, deep connections between family members separated by generations and location, “Daughters of the New Year” challenges its readers to remember that time is a construct. William Faulkner might’ve been onto something with: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Nguyen includes every member of her family with many of their favorite recipes and anecdotes. Their stories can be heartbreaking, like the death of her younger brother James in his 20s to stomach cancer. There are also hauntingly beautiful moments, like Zorn and Nguyen weaving the story of communicating love through the phrase “ăn cơm chưa,” or, “Have you eaten rice yet?”

“Đặc Biệt” sits on our counter, so bright and beautiful that it’s almost alive, wanting to burst out of its spine. It’s alive with color, but also the memories and traditions of Nguyen’s elders captured in its pages.

Boosting flavor the “Đặc Biệt” way

“Đặc Biệt” gets the Chop It Up stamp of approval for packing a lot of flavor on a budget. Many of the recipes utilize staples championed in this column before, like fish sauce, fermented shrimp paste and the power of crunchy, roasted nuts. Once your kitchen contains a few staple ingredients, you can execute many of these dishes by adding your protein of choice and focusing on in-season fresh herbs and vegetables.

“Especially now, with the economy and everything, the average home cook needs to know how to be resourceful and learn new ways to use the same ingredients,” Nguyen said. “Most of the time, things that are on sale are in-season produce that they have a lot of and will go bad if they don’t sell it.”

She said that she keeps bouquets of fresh herbs in water in a vase at room temperature, so they will naturally start to sprout until you have new herbs.

“It’s great for thai basil and any perilla like shiso and mint,” Nguyen said. “The fresher the herb, the more likely it is that it will survive. Make sure that none of the leaves are in the water because the bacteria from the leaves is what makes it rot faster.”

Shiso and rau răm were highlights of the salad that accompanied Bún Chả Hà Nội at Nguyen’s dinner with Chanchaleune. Despite offering such dizzying complexity, the dipping sauce is basically: “Combine ingredients and reduce.” Chef Nguyen has shared the recipe with Streetlight’s readers.

Hà Nội-style vermicelli with grilled pork or Bún Chả Hà Nội (AKA “The Obama”) from “Đặc Biệt”

Serves 4 to 6

Ingredients:

Grilled pork belly:

- 2 pounds thinly sliced pork belly

- 1 teaspoon black pepper

- 1 tablespoon sugar

- 2 tablespoon fish sauce

Grilled pork patties:

- 2 pounds ground pork (make sure you get the fattiest option)

- 1 teaspoon black pepper

- 2 tablespoons sugar

- 2 tablespoons fish sauce

- ½ of an onion, finely grated

- 1 teaspoon kosher salt

Dipping sauce:

- 1 cup white vinegar

- 1 cup sugar

- 1 carrot sliced thinly into half moons or any shape

- 1 daikon sliced thinly into half moons or any shape

- 5 cloves garlic

- 5 Thai chili peppers

- 1 cup fish sauce

Accouterments:

- One 400-gram package vermicelli rice noodles, cooked according to package instructions and immediately drained and rinsed with cold water afterward.

- 1 head green leaf lettuce, shredded

- 1 bunch cilantro, roughly chopped

- 1 bunch mint, leaves picked

- 1 bunch basil, shiso or rau răm

To make the grilled pork belly:

- In a bowl, combine the pork belly, black pepper, sugar and fish sauce with 2 tablespoons of water. Marinate for at least 30 minutes.

- Lay the pork belly into a grill basket or skewer it to grill. Grill the meat on a high-flamed grill, being careful as the fat will want to catch the pork on fire. If you don’t have access to a grill, make a layer of pork belly on a sheet tray and place under the broiler on high for 5 minutes, flip the pork and cook for another 4 to 5 minutes or until edges are nice and brown and meat is fully cooked.

To make grilled pork patties:

- In a bowl, thoroughly combine the ground pork, black pepper, sugar, fish sauce, grated onion and salt. Chill for at least 30 minutes.

- Form into 2-inch patties and grill them until a thermometer reads 150 degrees in the center or pan-fry them on a medium-high heat for about 4 minutes on each side or until it reaches 150 degrees in the center.

To make dipping sauce:

- In a saucepot, combine the vinegar, sugar and 4 cups of water, and cook over medium heat just until the sugar dissolves. Cut the heat. Add carrots and daikon to the pot.

- Crush the garlic and chilies together using a mortar and pestle. Add to the carrot and daikon, along with the fish sauce. Portion into bowls and serve warm.

To build the bowl:

- Combine the lettuce and herbs altogether to be used like a salad for the dish.

- Place 1 cup of the sauce with some carrots and daikon into a medium-sized bowl. Add in some cooked pork patties and pork belly. On a plate, place a handful of noodles and a handful of salad and serve that next to the grilled meats in sauce.

Chop It Up is a monthly column from Jacob Threadgill, a “semi-retired” journalist in Oklahoma City, where he wrote for the alt-weekly Oklahoma Gazette for three years. Prior to the Gazette, he wrote music and lifestyle features for The Clarion Ledger in Jackson, Mississippi.

Streetlight, previously BigIfTrue.org, is a nonprofit news site based in Oklahoma City. Our mission is to report stories that envision a more equitable world and energize our readers to improve their communities. Donate to support our work here.

Correction: This story was edited to note that phở grew in popularity after Clinton’s visit to Vietnam in 2000. Phở was already popular throughout Vietnam at that time.

Of course, Vietnamese cuisine is well-known for its many regional soup dishes: Phở, which includes Phở Gà: made with chicken, fewer spices, and less involved than its brother dish Beef soup: Phở Bò), Bánh Canh, Bún Bò Huế etc…Not to mention the many variants of Hủ tiếu (also used with flat rice noodles), Hủ tiếu Nam Vang, Hủ tiếu Mỹ Tho, Hủ tiếu (bà Năm) Sa đéc, etc. Note: the names followed Hủ tiếu are regions where the Hủ tiếu dishes originate, e.g. Hủ tiếu Nam-Vang: Pnom-Penh (Cambodia)

But to say that other Vietnamese soup dishes blow Phở out of the water is a personal hyperbole! Culinary delights and Tastes maybe an acquired choice/preference. That said, Phở – if ones care to conduct a scientific survev – in all probability, is the most popular Vietnamese soup worldwide!