There just isn’t enough room.

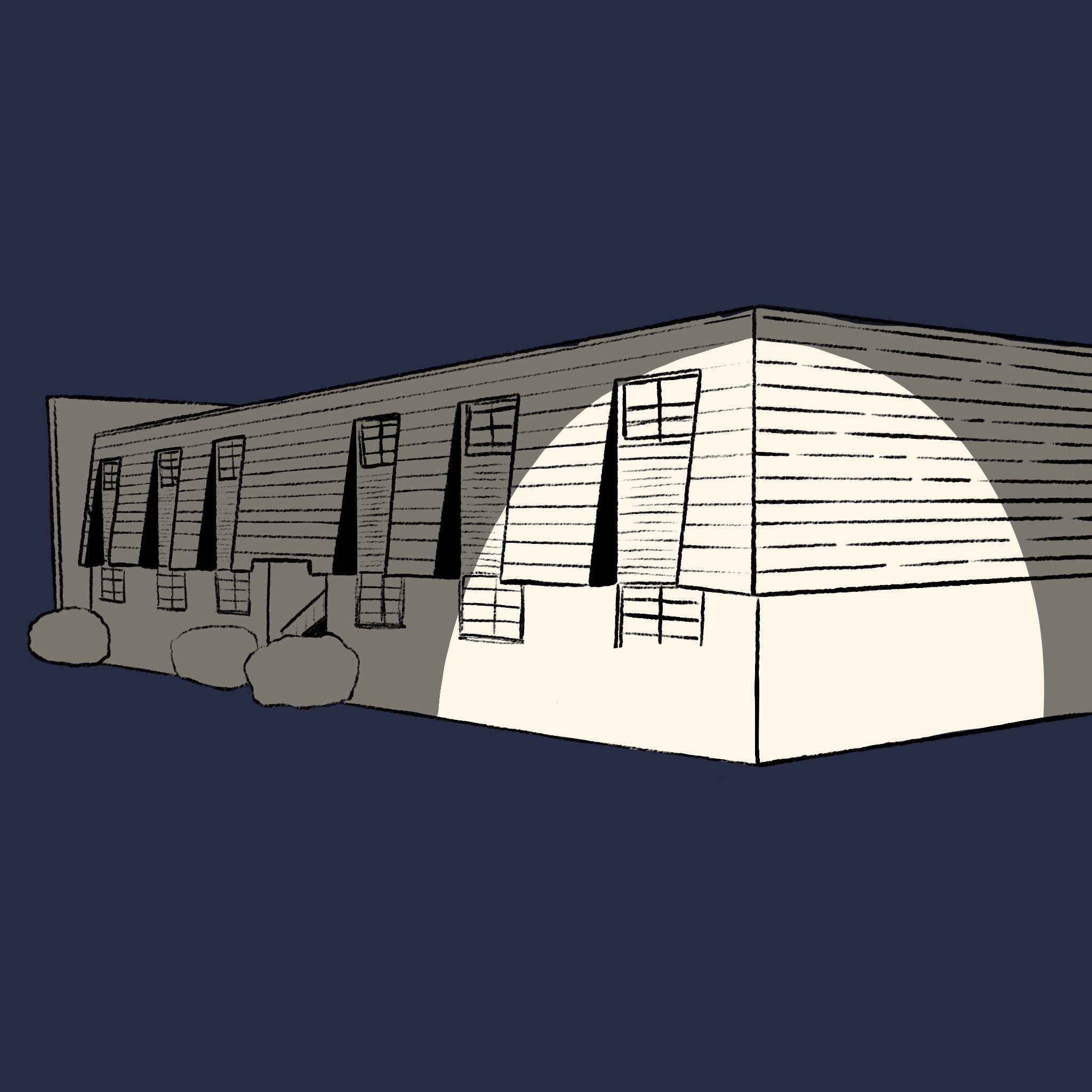

April Doshier, executive director of Food and Shelter in Norman, Oklahoma, said the nonprofit’s 52-bed shelter, A Friend’s House, is full “every single night.”

“We’re turning away 10 to 12 people a night who have no other option but to sleep outside,” she said. “We hear from a lot of folks that they don’t even go because they already know before they get there it’s going to be full.”

If they can’t get space in the shelter, they look for another safe spot, but Doshier said those places are getting harder to find as city staff and police departments face pressure to tear down campsites.

Adding to that pressure, on Friday, Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt signed into law a measure that will make it a misdemeanor to camp on state property.

“There’s a growing apathy, a growing sense of frustration and hopelessness for people who are on the street,” Doshier said. “That comes from, not just that inability to find a safe place to sleep, but the things that they hear, the vitriol on social media that plays in and impacts them.”

Homelessness has risen nationally since 2017, and last year, the number of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness reached an all-time high of 256,610 people, according to the US Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) annual homeless census, the point-in-time count.

According to the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, unsheltered homelessness has grown both in expensive states and those that have historically had low costs of living, like Tennessee and Texas.

In 2023, 396,490 people were staying in shelters, a 14% increase from the year before.

Many of them were relying on emergency shelters, places that provide temporary shelter to people experiencing homelessness without requiring them to sign a lease or occupancy agreement.

Some service providers told Streetlight that after years of rising rents and a shortage of affordable housing options in their communities, more people are becoming homeless and for longer periods of time.

A greater need for homelessness services is straining shelter systems in some mid-sized and smaller communities, where demand is outpacing shelter capacity.

Mary Frances Kenion, vice president for training and technical assistance at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, said some communities are also feeling a “post-pandemic whiplash” with the loss of covid relief funding that could be used for emergency shelter and other housing programs.

“We’re in a position where our social safety net is not able to keep up, just because of the new instances of homelessness every week in communities across the country,” she said. “Preventing homelessness and addressing it quickly before it occurs is the road we want communities to take.”

Data shows homelessness is growing faster than shelter resources

From 2022 to 2023, the number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States rose 12%, while the nation’s supply of emergency shelter beds increased 7%.

Streetlight analyzed 2023 point-in-time count data, the most recent available national data on shelter capacity, to determine communities’ shelter gaps—the difference between year-round shelter beds and the unsheltered population.

During the point-in-time count, 653,104 people in the United States were experiencing homelessness, while 449,567 year-round shelter beds were available—an estimated shelter gap of more than 200,000 beds.

That said, some unsheltered people still wouldn’t be interested in shelter if it were available, and communities might not consider building more shelters the right choice to reduce homelessness, especially in the face of other spending needs.

[ Read more of our housing coverage ]

Those issues came up last week during oral arguments in City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Johnson, a case asking the Supreme Court to reverse a ruling that blocks cities from banning camping on public property.

“Many people have mentioned this is a serious policy problem,” Chief Justice John Roberts said. “And it’s a policy problem because the solution, of course, is to build shelter to provide shelter for those who are otherwise harmless. But municipalities have competing priorities. … Which one do you prioritize?”

Kenion recommends that if communities increase shelter capacity, they also invest in pathways to permanent housing.

“This is not something we can shelter our way out of,” she said. “People who are in shelter are still without a home. Shelter can also be very costly, not just from a bricks and mortar perspective, but because many shelters are staffed for 24/7 operations, and that comes with a cost.”

Shelter demand is heightened during severe cold weather

Many communities face their biggest need for shelter during cold weather, when temperatures are too low to sleep outside safely.

Erin Read, executive director of the Knoxville-Knox County Office of Housing Stability in Tennessee, said most of Knoxville’s shelters don’t serve families, and the area doesn’t have a low-barrier shelter, a type of shelter that doesn’t require clients to be sober, attend religious programs or follow other rules that might deter them from receiving services.

Knoxville’s largest shelter can house about 400 people, and Read said it usually hits capacity during the winter.

[ Read more: When subsidized housing isn’t safe, renters struggle to get help from HUD ]

Last summer, the housing stability office started developing its first emergency plan for cold weather. If an upcoming forecast predicts temperatures will hit 25 degrees or under, three churches and the Salvation Army Knoxville gym serve as warming centers.

In January, a week-long winter storm set a Knoxville record for the most days in a row with at least four inches of snow. During the “snowpocolypse,” Read said, Knoxville’s largest shelter hit capacity quickly, and the cold weather plan went into effect for the first time.

“Every single church was at one and a half to two times their stated capacity, but we made it work,” she said. “We had space for every single person who wanted to be inside.”

Sheltering pets during cold-weather events can be especially challenging.

Norman, Oklahoma’s shelters don’t serve people with companion animals, so during a January winter storm, Food and Shelter paid about $40,000 for more than 80 motel rooms to house clients with pets, Doshier said.

Adding to shelter capacity—and aspiring to

Using 2020 point-in-time count data, Pierce County, Washington estimated a need for about 2,300 emergency shelter beds in its 2022 plan to end homelessness. By its 2023 point-in-time count, the county had added about 600 emergency shelter beds for a total of 1,632 beds.

A Pierce County website tracks emergency shelter availability in the area every day. On Friday afternoon, it showed space was available for 32 individuals and 20 families.

Delmar Algee, social services supervisor for Pierce County, said congregate shelters in the county are usually about 80% full, while non-congregate shelters that provide private units or rooms are typically 95% occupied. Safe parking sites, where people experiencing homelessness can park overnight, are also usually almost full.

[ Support our journalism by making a tax-deductible donation to Streetlight ]

Algee said the county is listening to people experiencing homelessness “and learning we need to have more of a menu of options.”

“Our goal is to be able to capture whatever household type is literally homeless by HUD’s definition, on the streets and in need,” he said. “So if it is someone that has a pet or if it’s a couple, we would have a place for them to go.”

The News Tribune reported last month that three emergency shelters are opening in Pierce County later this year, including a Tacoma shelter with 65 medical-respite beds.

Smaller communities are also seeing a need for more shelters.

In Mitchell, South Dakota, with a population of about 16,000, service providers say they’re seeing a bigger demand for assistance from people experiencing homelessness.

SDPB Radio reported last year that the city has a shelter for domestic violence survivors, but the closest emergency shelter is in Sioux Falls, about an hour away.

Assistance is also available from government sources like Davison County. The county sometimes provides people experiencing homelessness with gas money, a hotel room or bus tickets to Sioux Falls or Vivian to go to medical appointments, visit sick family members or for other reasons, Davison County Auditor Susan Kiepke said.

[ Read more: Criminal records can lock people out of housing assistance. HUD’s creating new rules to help ]

A new nonprofit, Home for Now, has been advocating for creating an emergency shelter in Mitchell. Matthew Richards, Home for Now’s president and pastor of the Congregational United Church of Christ, said a 20 to 30-bed shelter would help the community address what he sees as a growing need.

“Things are really beginning to move in a direction that allows for more of an open conversation when it comes to mental health, homelessness and addressing the stigma that so many people have (toward) what homelessness entails,” Richards said.

How to invest resources to reduce homelessness

Read said in Knoxville and Knox County, a discussion has emerged around what level of resources should go toward managing homelessness, versus ending homelessness.

“We do want to have a shelter system that works and serves everybody it needs to serve, but that’s only part of the equation,” she said. “The other part is actually a lot harder, and that is trying to ensure that we have viable housing options for people to step out of homelessness.”

Doshier said Norman should have a holistic approach to homelessness. That includes providing permanent supportive housing for people considered chronically homeless and addressing the inflow into homelessness with prevention and diversion programs.

“We do have to have a safe place for people to sleep at night by investing in more emergency shelter beds,” Doshier said, “Really that goes back to basic human needs. We can’t ask people to do big things if they aren’t able to sleep safely at night.”

This story’s data visualization was developed by Josh Stovall.

Contact Streetlight editor Mollie Bryant at 405-990-0988 or bryant@streetlightnews.org. Follow her reporting by joining our newsletter.

Streetlight, previously BigIfTrue.org, is a nonprofit news site based in Oklahoma City. Our mission is to report stories that envision a more equitable world and energize our readers to improve their communities. Donate to support our work here.