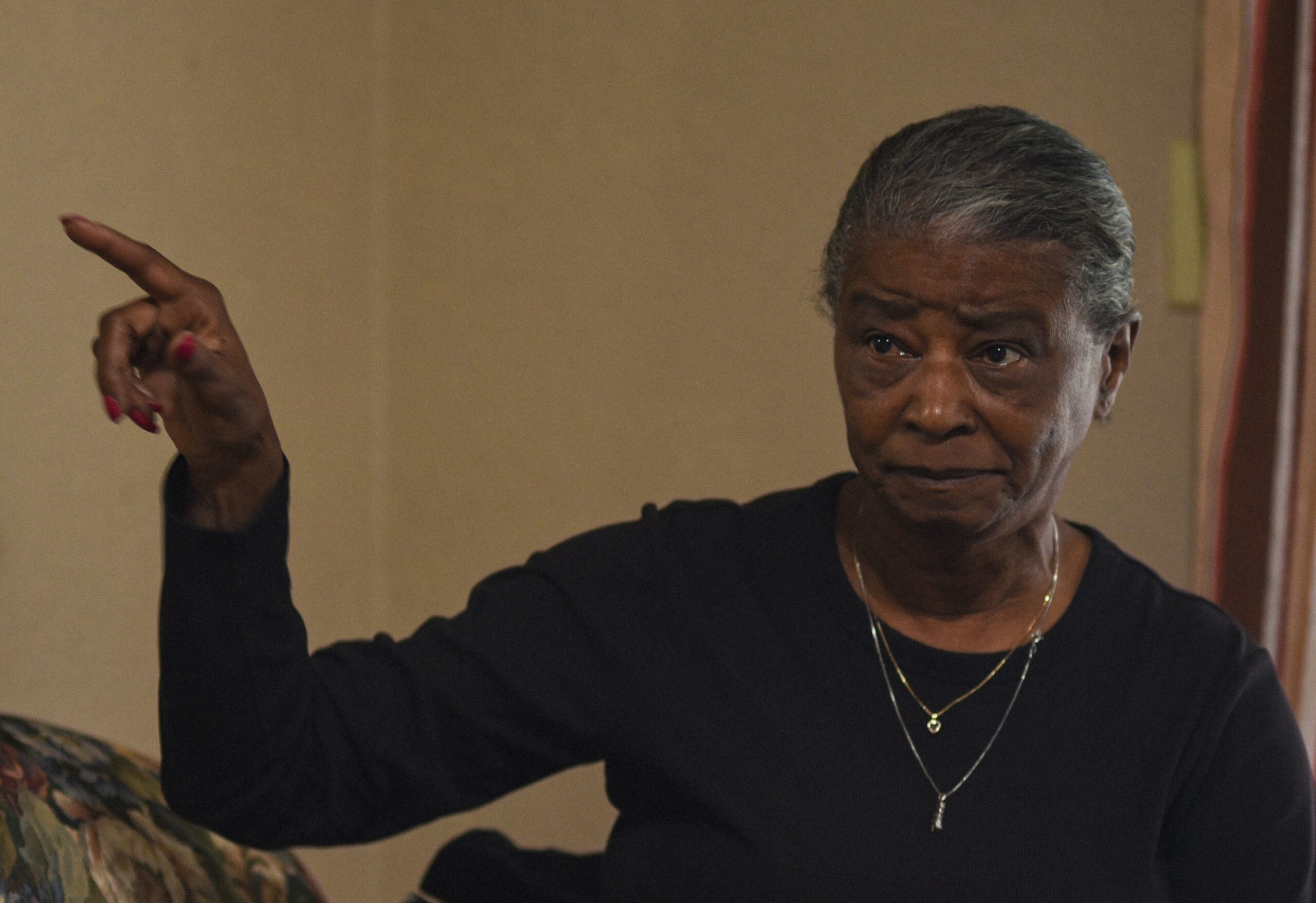

Dianne McDaniel, founding president of the JFK Neighborhood Association, still remembers the tight-knit bond she and her neighbors forged after she moved to the Oklahoma City neighborhood in 1985.

“The neighbors would garden and give me some of their okra and tomatoes,” she said. “Everybody looked out for everybody. The environmental issues that we faced were not quite evident until maybe three or four years after we moved in.”

Chemical smells from industrial facilities—sulfur, ammonia and other unnamable but piercing odors—rode on northbound winds to waft into the neighborhood. One day, McDaniel found an odd, dusty residue clinging to the leaves of her beloved pink crepe myrtles. And then came the “sonic booms” from nearby scrapyards—soul-shaking explosions that McDaniel and other JFK residents have said for years are unpredictable, disruptive and damage their homes.

“We need some immediate action,” McDaniel said of the environmental hazards that continue to plague residents despite years of the JFK Neighborhood Association advocating for improvements. “Why does it have to take this much to get things done when it’s affecting so many?”

Asked if the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has done enough to help the neighborhood, McDaniel said: “I’m not going to say they don’t care, but the problem has existed so long, and it’s been marginalized, I think, because of who we are.”

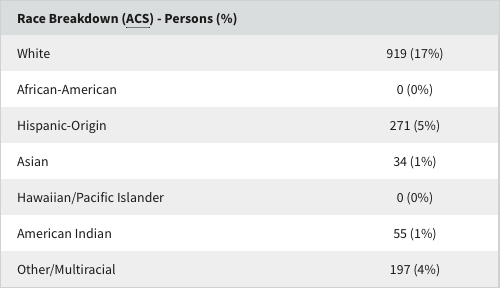

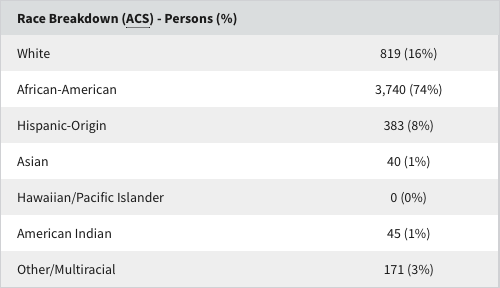

Most residents in the JFK neighborhood are Black, Census Bureau records show. But until queries from Streetlight on Tuesday, EPA’s data on all but two of 34 industrial sites under EPA oversight in the neighborhood’s zip code falsely claimed no Black people lived within one mile of the facilities.

A Streetlight investigation found the error affected information on EPA-regulated sites in the JFK neighborhood, eight majority-Black cities across the country and most other facilities in the ECHO system, which stands for Enforcement and Compliance History Online.

JFK residents, an academic researcher who has studied racial health disparities in the neighborhood, and the EPA itself said the data was incorrect. But it’s unclear why such an error would erase data on a single race.

Streetlight asked the agency why the error existed on Tuesday morning, and by the end of the day, the EPA had altered data previously viewed by Streetlight to include the number of Black people who live within one mile of the sites.

Jeff Landis, a spokesperson for the EPA office that oversees the ECHO system, told Streetlight on Wednesday: “After looking into it, we confirmed that this is a bug in the front-end coding within the detailed facility report. We are working to get it remedied as soon as possible.”

On Tuesday, press secretaries for House Speaker Mike Johnson (R-Louisiana), Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), president pro tempore for the Senate, and Rep. Tom Cole (R), who Oklahoma Watch reported has worked to prevent EPA cuts to his district, didn’t respond to emails seeking comment on the data and asking if they find it appropriate to exclude an entire racial group from EPA data.

Without data on Black residents, white people falsely seem to be most affected by toxic sites

The ghost data was in EPA reports on individual sites in the agency’s ECHO system. Facilities in the system include factories, Superfund sites and other EPA-regulated businesses.

EPA’s ECHO search says the system can be used to investigate pollution sources and analyze enforcement trends.

Until Tuesday, 106 out of 114 site profiles viewed by Streetlight since last week included no numbers for Black residents living within one mile of the facilities—often despite Black people making up the majority of people living close to the sites.

Instead, the vast majority of the summaries—which are the easiest and fastest way for most members of the public to access demographic information about the sites—falsely said zero Black people lived within one mile.

No other race was excluded from the summary pages in the dozens of site pages reviewed by Streetlight.

By excluding data on Black residents, white people often falsely appeared to be the largest racial group living near the toxic sites, despite BIPOC community histories and decades of research proving that is not the case.

In 1994, President Bill Clinton issued an executive order that directed federal agencies to address disproportionate environmental and health impacts affecting BIPOC and low-income communities. That order led to EPA’s 2021 creation of EJScreen, a mapping and screening tool that combined environmental and demographic data.

In February, the EPA removed the EJScreen tool under an executive order President Donald Trump issued on his second day in office, which revoked Clinton’s order from decades earlier. Also in February, the EPA put 168 staffers focused on environmental justice on administrative leave.

Another Trump executive order from April directed Attorney General Pam Bondi to stop enforcing state laws and civil actions involving environmental justice and climate change. The order also instructed Bondi to identify “illegal” state environmental justice laws and recommend “Presidential or legislative action necessary to stop (their) enforcement.”

Black Americans, zoned into homes near industrial facilities for over a century, bear the brunt of health impacts from pollution

The federal government and EPA have known for decades that toxic sites and pollution have disproportionate health impacts on BIPOC communities, who are more likely to live near industrial facilities and Superfund sites.

On EPA’s summary pages for each facility, the demographic section says: “ECHO compliance data alone are not sufficient to determine whether violations at a particular facility had negative impacts on public health or the environment.”

A 2021 study in Science Advances from the EPA-funded Center for Air, Climate and Energy Solutions found that people of color breathe more particulate air pollution than white people on average. Researchers studied data from 48 states and found that on average, Black people were exposed to this pollution at higher rates than white, Hispanic and Asian people, with 77% of Black people exposed, compared to 29% of white people.

Particulate air pollution is the No. 1 environmental cause of death, according to the study, and it’s responsible for 85,000 to 200,000 deaths per year in the United States. An EPA write-up on the report said exposure to this kind of pollution can cause lung and health problems, especially for kids, older adults and other vulnerable groups.

Carrie Leslie, a faculty lecturer at the University of Oklahoma, studies the impacts of discriminatory zoning—the legacy of policies like redlining that steered segregated BIPOC communities and industrial facilities linked to pollution into the same areas, creating health disparities that have endured for generations. Leslie said greater exposure to toxins like those found in air pollution can compound racial health disparities.

“Ensuring that the demographic data regarding racial and ethnic populations is accurate is critically important to providing evidence and documentation of environmental injustices or disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards or pollution for communities of color or BIPOC communities,” Leslie said. “It is crucial to identify which facilities or industries are responsible for these environmental health inequalities. And you should not have inaccurate data.”

Why didn’t the EPA factcheck its data?

In 2008, Jeff Trevillion Jr., an Oklahoma City attorney, moved to the JFK neighborhood because of its affordable lots and location near downtown. He didn’t know about the industrial presence in the area at the time.

“None of that was disclosed in our closing paperwork or anything,” he said. “We were there maybe six months or so before we heard our first explosion.”

Trevillion didn’t learn the cause until about a year later, and it’s been an annoyance ever since. One explosion left a light fixture hanging by wires from the laundry room ceiling. Like other residents, he’s wondered how industrial sites in the neighborhood have affected his family’s health and if they might be linked to his battle with asthma.

Asked about EPA’s missing data on his neighborhood a few hours before it was restored, Trevillion said: “It just makes me wonder why someone would make a false report like that. What do they benefit from that?”

He also wondered about the missing data on Black residents living near EPA-regulated sites in majority-Black cities, including Jackson, Mississippi; Baltimore, Maryland; and Memphis, Tennessee.

“Why was there no factchecking?” he asked. “Is it because it is marginalized Black communities that are not prioritized on anything? Is that why they can make a statement like that and no one challenges it?”

Contact Streetlight editor Mollie Bryant at 405-990-0988 or bryant@streetlightnews.org. Follow her reporting on Bluesky or by joining our newsletter.

This article was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Streetlight is a nonprofit news site based in Oklahoma City. Our mission is to report stories that envision a more equitable world and energize our readers to improve their communities. Donate to support our journalism here.