Ever since Donald Trump became president a year and a half ago, national news organizations have done their best to understand why. They’ve crunched numbers, pored over graphs and studied what makes the ineffable Trump voter tick. Along the way, they’ve developed an array of theories, some of which do little to quell conservative critics who say the national media is out of touch with regular Americans.

The latest iteration of this is a Politico piece published yesterday that found Trump did better than his predecessor, Mitt Romney, in “news deserts,” a term for places with the lowest newspaper subscription rates in the country. ProPublica reporter Alec MacGillis said on Twitter that Politico’s use of data “totally affirms what I saw on the ground in 2016.”

The article, written by Shawn Musgrave and Matthew Nussbaum, doesn’t mark the first time the link between low engagement with local news and high support for Trump has been explored, but it’s the first time I’ve seen data used to back up the claim.

Even though I agree there is a link, the Politico article feels more like an opinion piece to me than data reporting, part of an ongoing attempt to explain away the election. Moreover, I don’t believe you can count on newspaper circulation to explain Trump’s overall performance in the 2016 election.

A good place to start is with the term “news desert.” A similar phrase, food desert, describes a place with low access to affordable, nutritious food. It doesn’t mean people who live in a food desert can’t find any food at all. There might be fast food on every corner, but that isn’t the same as a healthy, low-cost meal that includes things like vegetables.

People don’t exist in a vacuum where local newspapers are their only option. We have a lot to choose from, and the healthy, nonpartisan stuff sometimes costs more than the partisan and hyperpartisan stuff. Breitbart, for instance, is totally free.

People across the country are choosing national (and partisan) media sources over local news, and I think reframing the issue to focus on that would avoid some of the pitfalls of Politico’s piece.

Here are two rules of thumb for causal relationships. First, for two things to have a causal relationship, that cause and effect need to keep happening across a wide variety of circumstances. In other words, if the effect can happen without the cause, then it isn’t much of a cause.

The second thing: Let’s say that A causes B. That means that the more A happens, the more B happens. If there’s less of A, then there’s less of B.

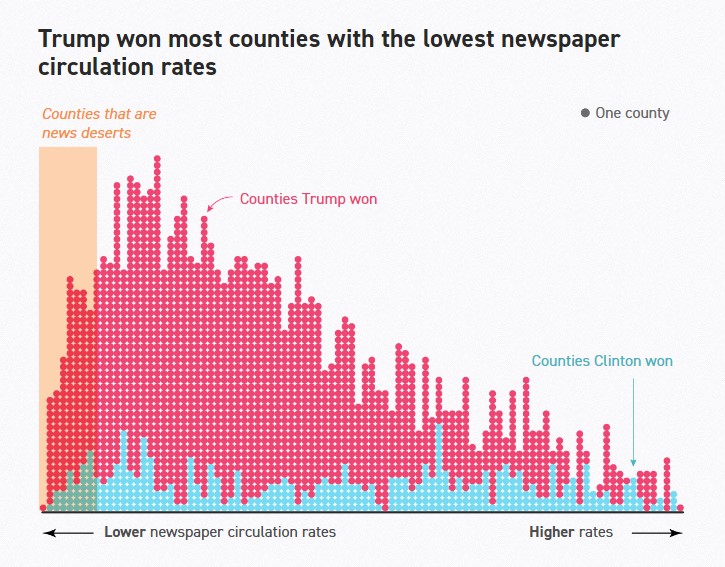

Politico’s data doesn’t fit with either of these rules. The reporters fail to explain why Trump did well in areas that aren’t news deserts, and he did, which you can see in this graph.

The graph, which omits the actual circulation rates, shows that as subscription levels increased at first, Trump’s performance was the same or better than it was in the news deserts. This applies to about half of the graph. Only then does his support start to go down. If there’s truly a relationship, his wins should instead decrease consistently as subscription rates increase. They don’t. And tellingly, Hillary Clinton’s wins don’t seem to be affected by subscription rates at all.

All that said, an obvious issue with news deserts is that they may cause people to lose touch with how national issues affect them locally, but the battle to cover national issues from a local angle has been lost in many newsrooms across the country already.

What I’m talking about here is the dearth of a White House press corps reporting to local newspapers. It’s something no one talks about any more, and Musgrave and Nussbaum either ignored or are unaware that this used to be a thing. Instead, they describe a past, remarkably similar to the present, where local papers get their national news fix from wire services and syndicated national columns.

“The editors lived in the communities they served, and went to the same churches and parent-teacher meetings that their readers attended,” Musgrave and Nussbaum wrote. “So when they decided to publish a story about national politics, it had a local stamp of approval: The local newspaper editor — and, in a similar way, the local TV anchor — were validators for national political coverage by reporters thousands of miles away.”

What’s better than “a local stamp of approval” on stories written by out-of-state strangers? A newspaper’s ability to hire its own reporters to cover Washington and to craft their coverage in whatever way best serves the paper’s readers. By 2014, 21 states had no correspondents covering Congress. About 10 years ago, regional dailies from Des Moines, Hartford, Houston, Pittsburgh, Salt Lake City, San Francisco and Toledo closed their Washington bureaus, along with Cox, Advance Publications and Copley Newspapers. I think these cuts have had a greater long-term impact on Americans’ perceptions of federal government than news deserts alone.

But the main issue I have with Politico’s piece is that it altogether neglects the national media’s role in amplifying Trump’s message. During a point in history when Americans are the most reliant on national news orgs and during a crowded contest for the Republican nomination, the national media gave Trump far more ink, audio and air time than the GOP’s more unassuming candidates. This level of coverage contributed to his nomination.

I covered a few Trump rallies as a reporter for The Clarion-Ledger in Mississippi, and my perception on political coverage dramatically changed after a reporter for a national news organization told me they were encouraged to focus on politicians’ insults against each other. “This could be a good night,” he said, expecting Trump to react to some recent drama.

Who insults others more than Trump? He essentially patented nicknames for Clinton, Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, to name a few. Why take the high road when the reward is wall-to-wall coverage?

Politico’s piece is a perfect example of the national media’s unwillingness to accept its role in the election’s outcome. Nonetheless, the blame for a national election doesn’t lie with circulation numbers for local newspapers that don’t actually cover national news.

Contact Mollie Bryant at 405-990-0988 or bryant@bigiftrue.org. Follow her on Facebook and Twitter.

Follow Big If True on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Looks like sound interpretation of the data in the chart. I am not sure I believe in cause and effect anymore. I believe in influences, favorable conditions, necessary preconditions and catalysts or triggers. Anytime someone says one thing caused another if feels like a gross simplification of reality. Politicos conclusion clearly falls short of “cause and effect”.